I originally planned this article as just a highlight of the tug Ludington – A US Army LT tug built by Jakobson in 1943. This tug was built as a class, so I thought…why not expand it to include all the tugs, and a look at their history.

The Original Trio

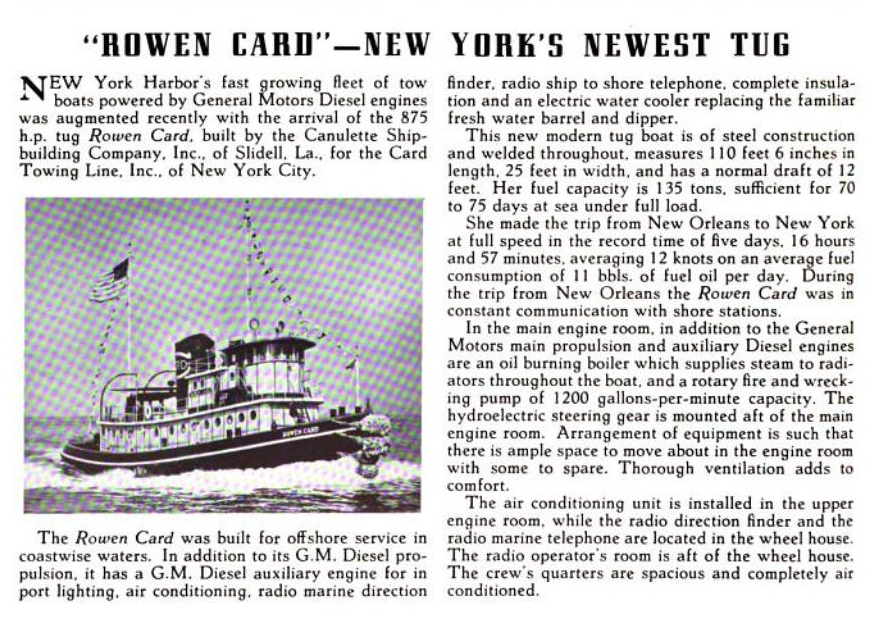

Stepping back a few more years to 1939, we begin with the Card Towing Line, and their brand-new tug Rowen Card. A general towing company in New York – Card had the Canulett Shipbuilding Company of Slidell, LA build them their new tug. This was an odd choice at the time, being the Northeast was littered with shipyards at the time. The Rowen was not a small tug either, she was a big girl at 110’ 6”, a 25’ beam and a 13’8” depth. While small for today, this was a first-class ocean tug of the era.

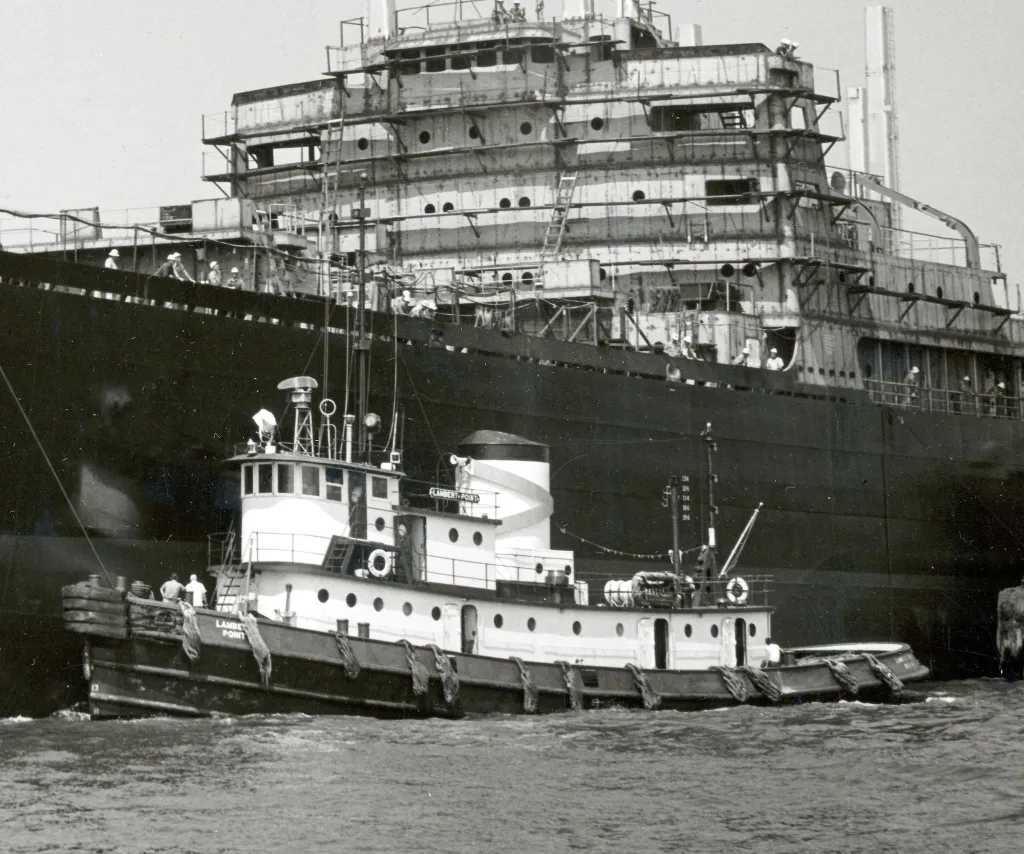

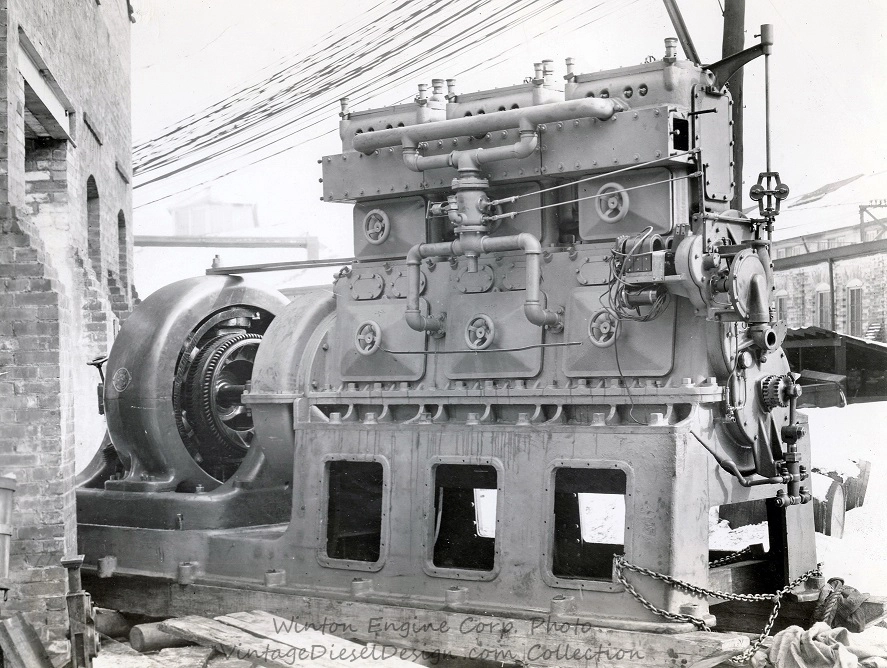

Propulsion for the Rowen Card is an interesting case in itself. While the Rowen was built in 1939, the engine…was built in 1925! It is unknown if the engine was resold by Winton, or if it was just a leftover floor model per se. The engine was a Winton 6-cylinder 128S. The 128S was a big engine: 16 ¾” bore with a 26” stroke. The direct reversing engine was rated for 875HP at 250RPM. Brand new for 1939, was a Detroit Diesel 3-71 30kW genset furnishing ships power. The tug had one extra amenity absolutely unheard of in tugboats – air-conditioned rooms.

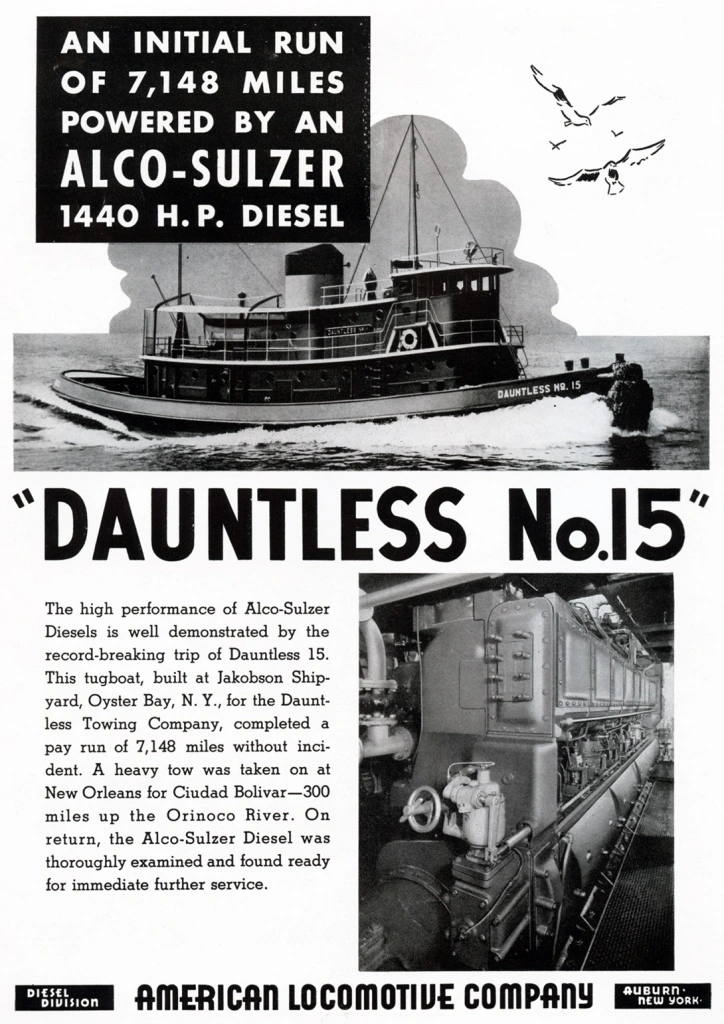

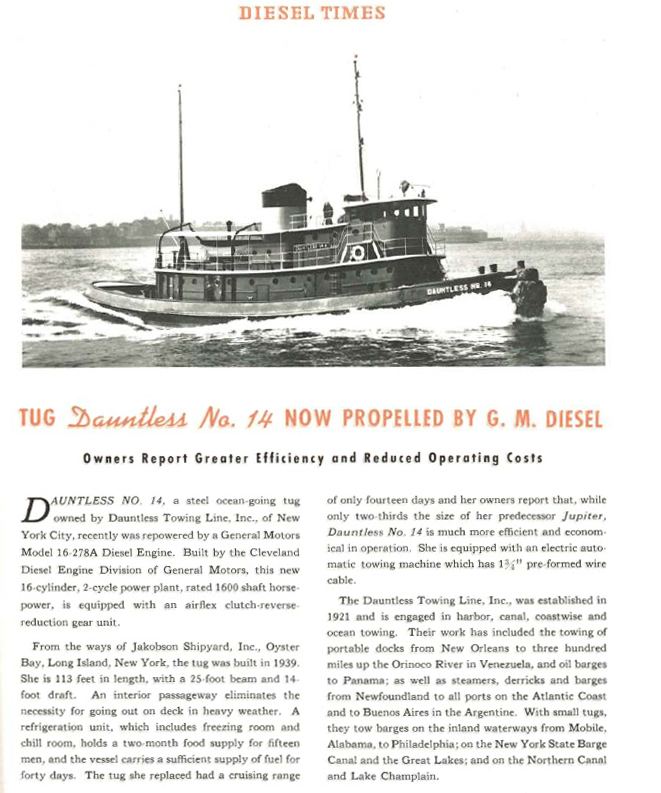

Shortly after (construction likely started around the same time) the Rowen was built, New York’s Dauntless Towing Line had their Dauntless #14 built by Jakobson Shipyard, in Oyster Bay, NY. The tug was identical to the Rowen with two exceptions. One – the Dauntless #14 was powered by an 8-cylinder Alco-Sulzer 8TM engine. In this era, all the period trade journals always referenced the engines by size, not model – something very frustrating for a historian! Thankfully I have enough resources in my files to dig around and find the actual model number. The American Locomotive Company was building Sulzer engines for marine and stationary use under license since 1935 through their subsidiary McIntosh & Seymour in Auburn, New York. Like the Winton in the Rowen, the Alco-Sulzer was a big direct reversing engine, with a 14” bore and a 23 ½” stroke, which made 1440HP at 279RPM. Unlike the Winton, the Alco-Sulzer was a 2-stroke engine, with a built-in pump scavenger (like a Fairbanks). The tug had a pair of shaft generators – one 25kW for ships power and one 45kW (more on that one later), both belted off the prop shaft. A Superior 6-cylinder GA6 engine with a 25kW generator was also in the engine room for when the tug was not underway.

The Dauntless #14 not long after delivery (top), and at work not long after towing a barge. Dauntless used a beautiful color scheme of bright red, with a buff stack. Both Photos – Dave Boone Collection

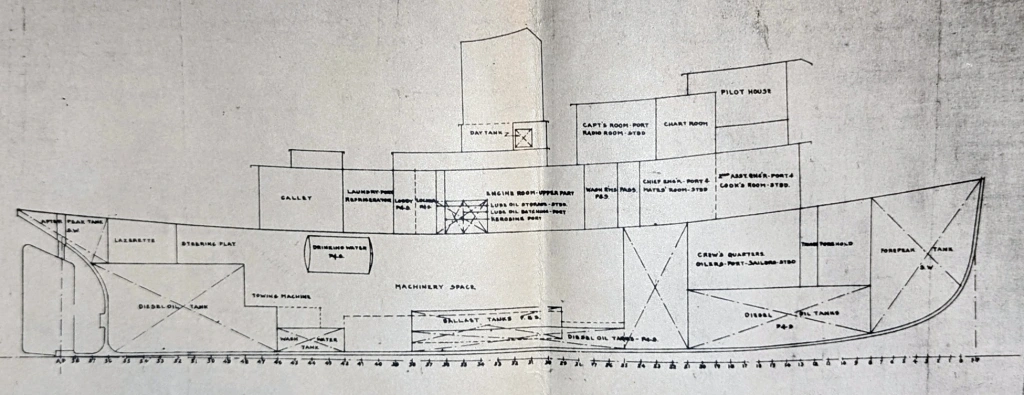

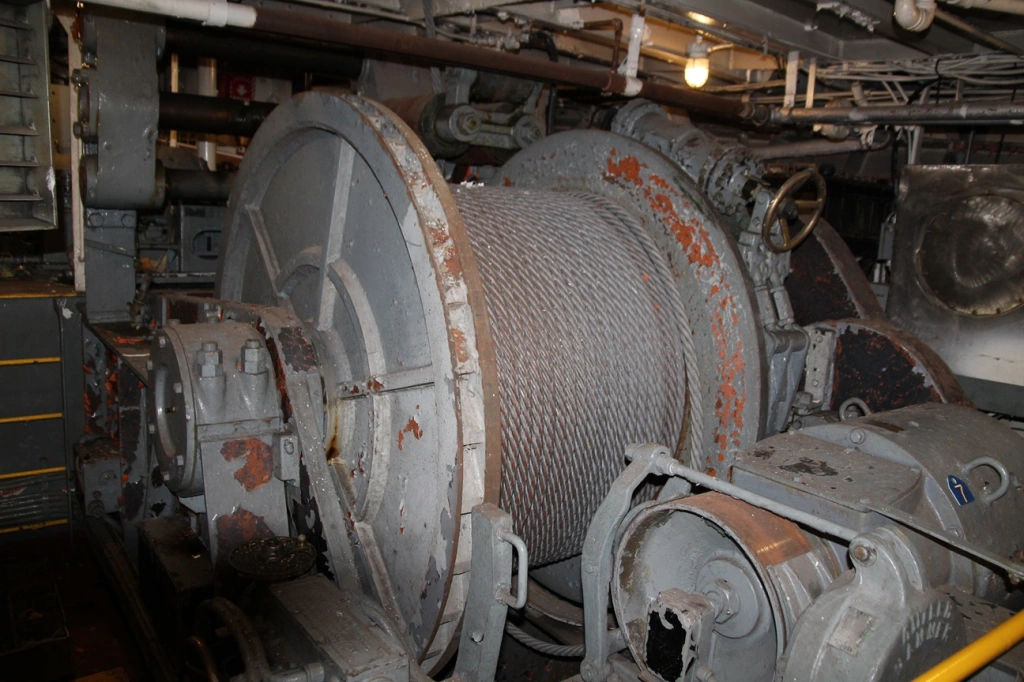

The other big difference was also in the engine room, but it was not an engine! That 45kW shaft generator supplied power for the 50HP Almon-Johnson automatic tension electric towing machine. The towing machine held 1200’ of 1 ¾” wire rope. The towing machine was mounted in the upper aft portion of the engine room, not only giving a nice chuck of weight for stability, but also protecting it from the elements on deck. The tow cable was routed up to the aft deck through a sheeve. The hull of the tug was stretched 3’ to 113’ long, to compensate for the larger engine and towing machine.

Dauntless Towing liked the Dauntless #14, so they ordered an identical tug in 1941, the Dauntless #15, also built by Jakobson and launched in August of 1941. One mystery remains – who designed these tugs? A 1941 article credits the design to Dauntless Towing – however the Rowen Card predated her design by a few months. The one Army drawing I have credits it to Cox & Stevens. I hope to do some more research in the future to hammer this out for sure.

The “new” Dauntless #15 was used for a series of promotional ads for both the American Locomotive Company, as well as Edison Batteries. It was common for all of the major component suppliers to run ads in trade journals that did features on certain new tugs – highlighting parts supplied on said tugs. While the same photo is in both ads – the tug is actually the Dauntless #14, retouched to be the #15. If you look close, the nameboard on the Alco ad still say Dauntless #14, however in the Edison one, the nameboard have also been retouched to match the hull.

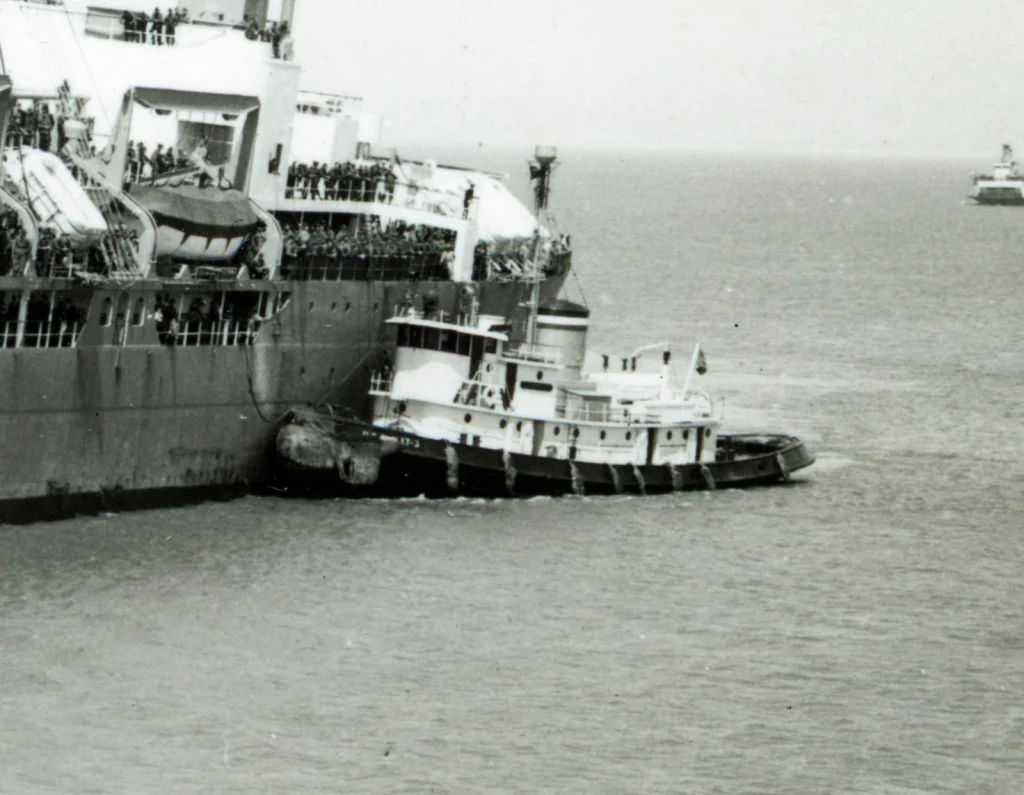

The Dauntless #15 at rest at one of NYC’s piers, and at work doing a ship assist. Dauntless was an all purpose company, and would do assist work as needed, typically alongside Moran tugs. Click for larger. Both Photos – Dave Boone Collection

The Army Takes Notice..

With the onset of WWII approaching, the tugs would not stay with their original owners very long. All three would be requisitioned by the Army/Navy in 1942/43. The Rowen Card became the Net Tender YNT-12/Tamaha, the Dauntless #14 became the tug YT-171/Yaquima and the Dauntless #15 became the Army Quartermasters tug Col. Albert H. Barkley.

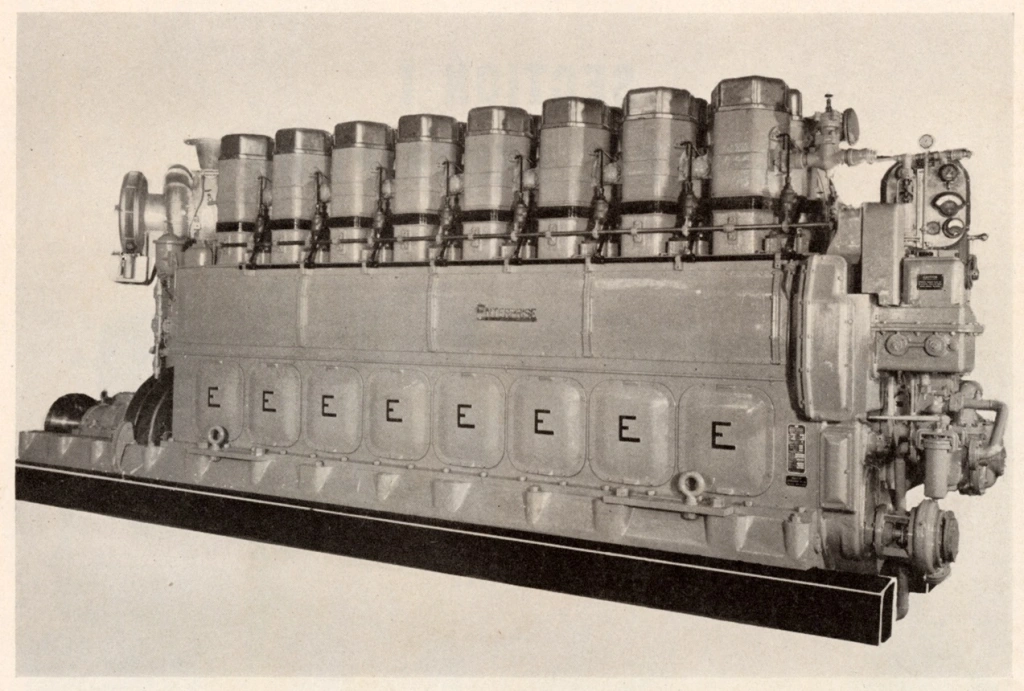

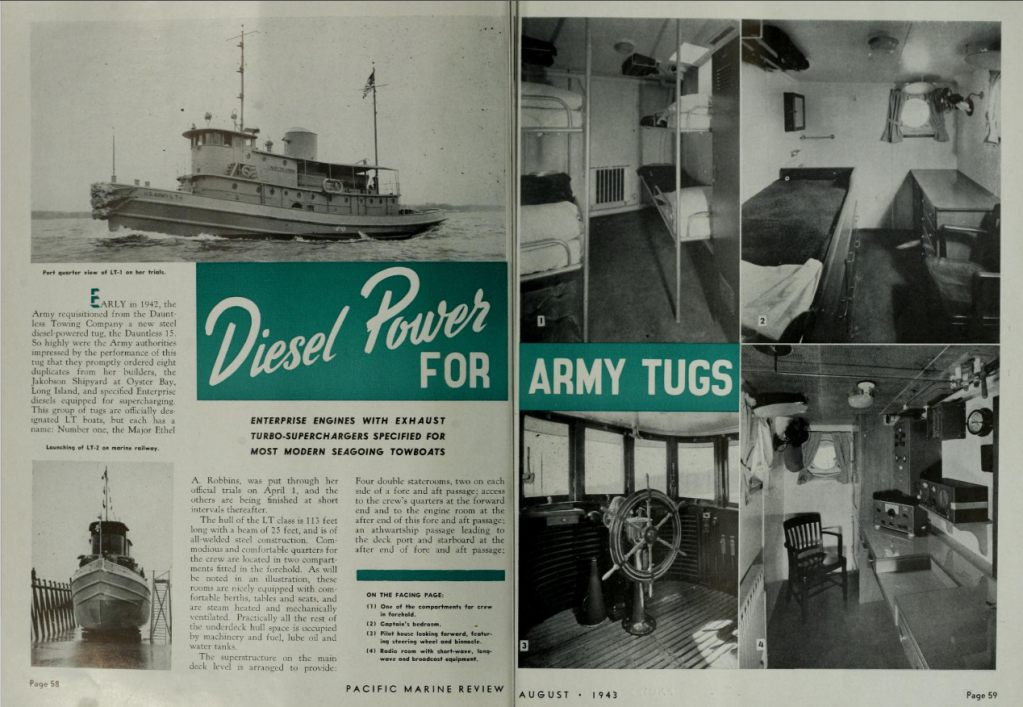

As it would turn out, the US Army was so happy with the Dauntless #15 that they opted to copy the design and build their own. Now known as Design #271, the order of 14 tugs was split with 8 going to Jakobson Shipyard, in Oyster Bay, NY and 6 going to Tampa Marine, in Tampa, FL. The tugs were the exact same design as the Dauntless #15, with the same specifications. The only change would be that all 14 tugs were powered by Enterprise engines. Everything else, right down to the Superior auxiliary generator, double shaft generators, towing machine and layout was all the same as the Dauntless #15.

I only have one drawing of these tugs. If anyone has a full set, I would really like to get a copy! Click for larger – VDD Collection

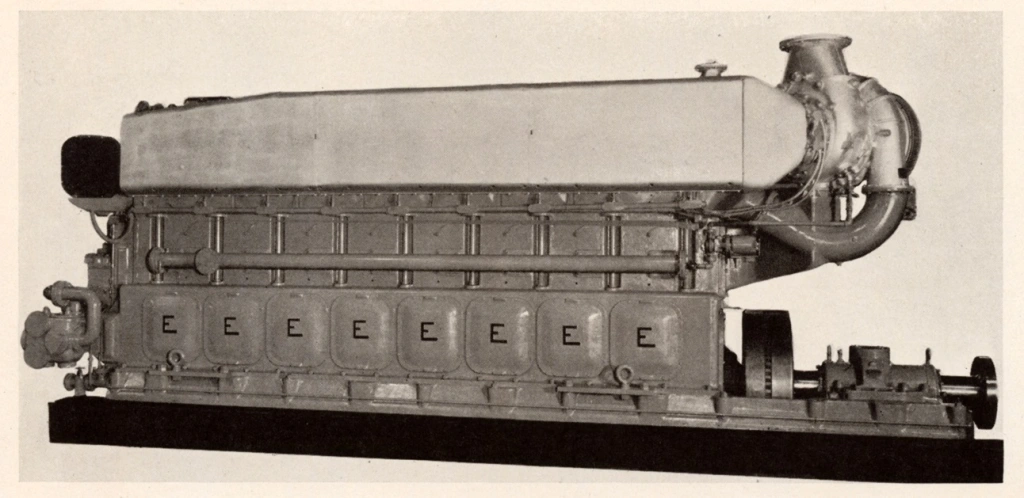

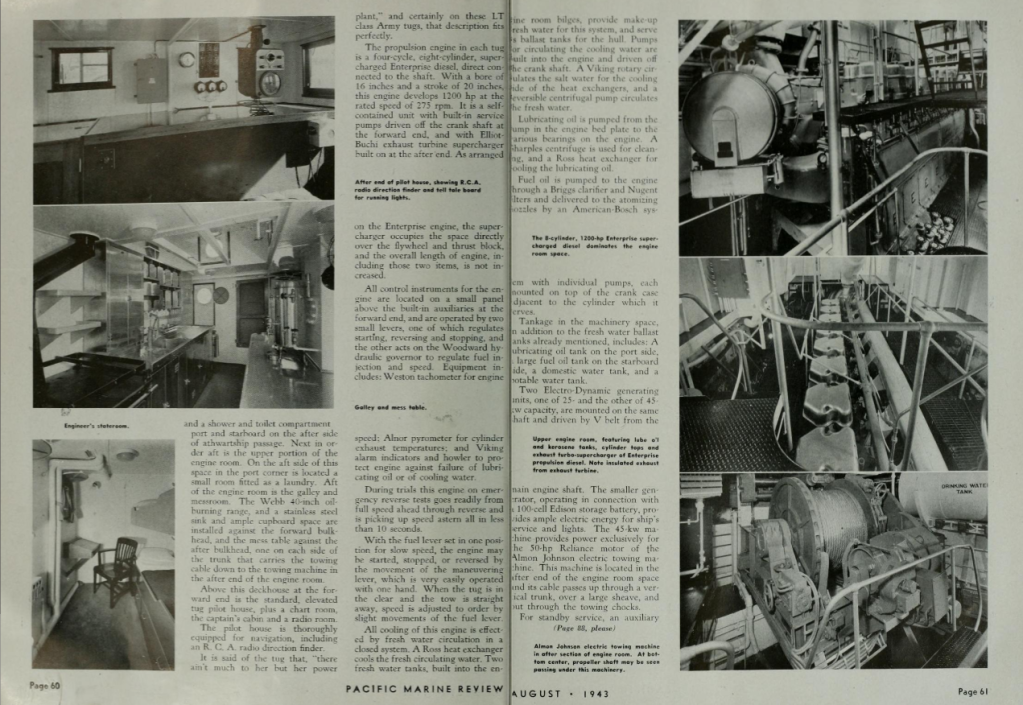

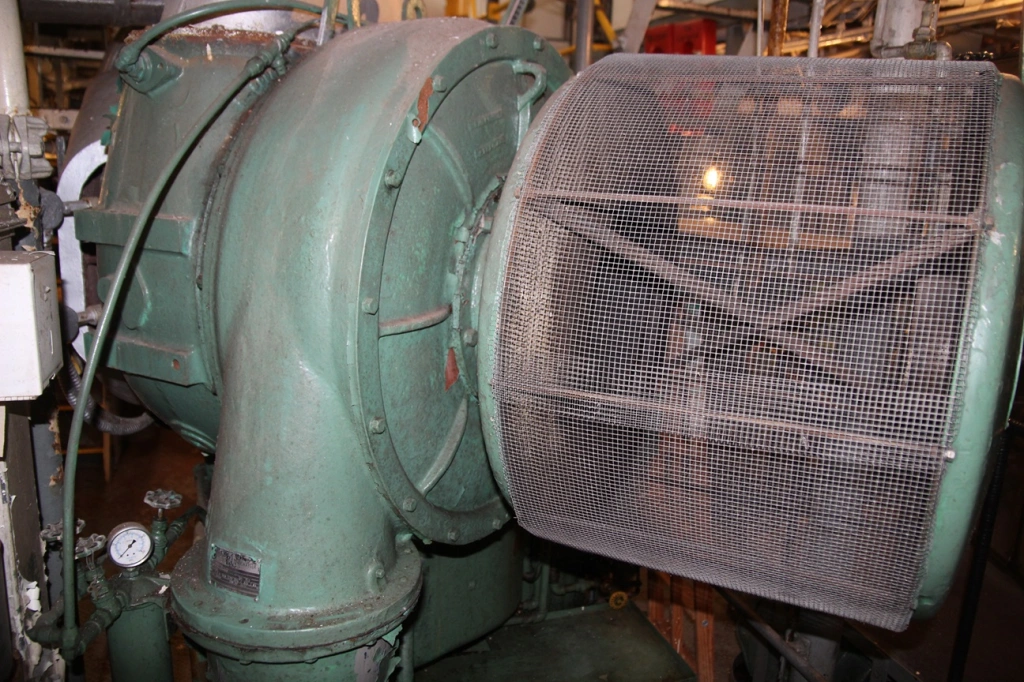

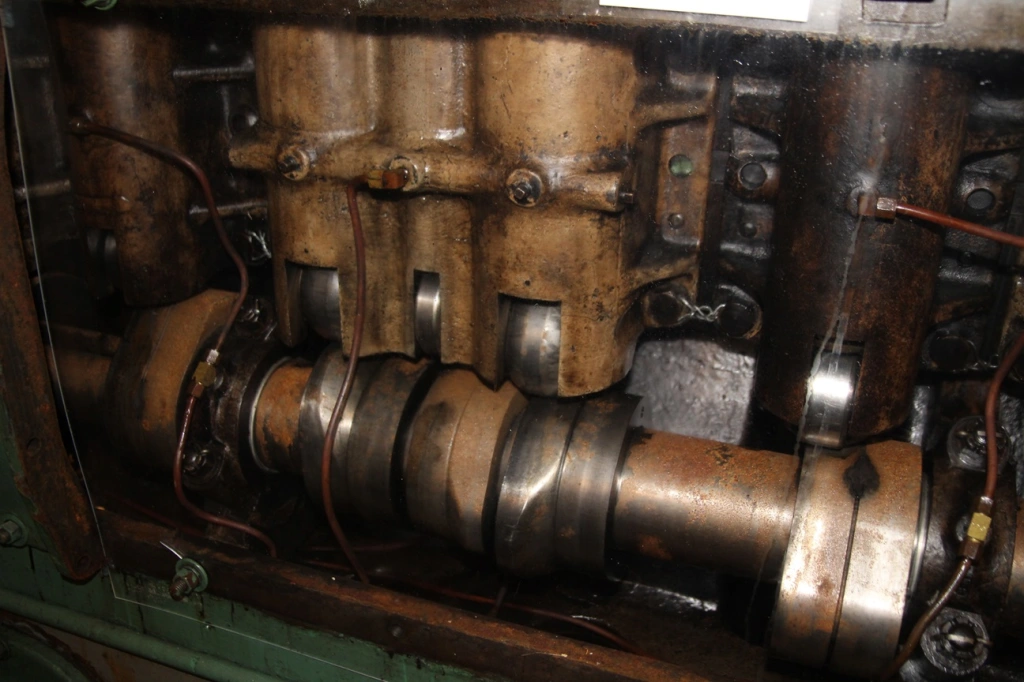

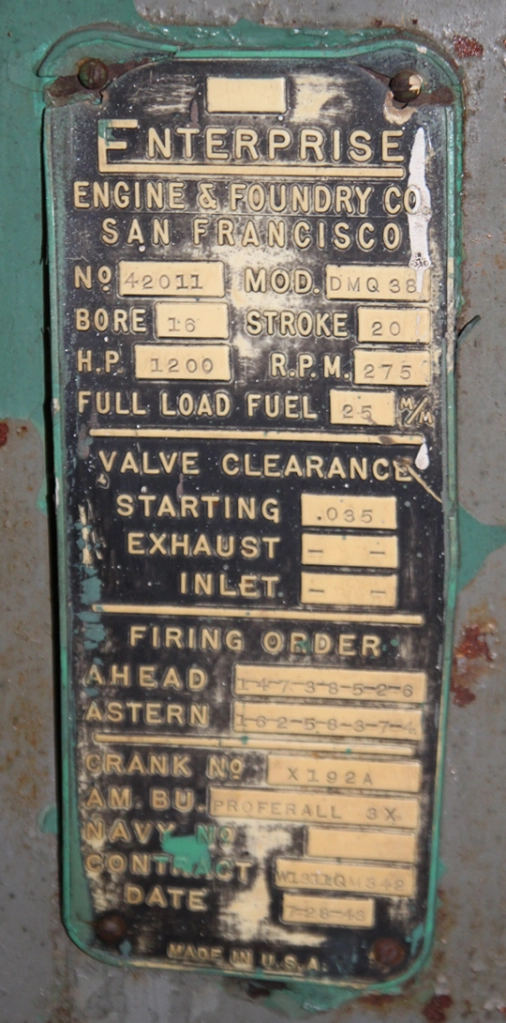

The tugs used an Enterprise DMQ-38 engine. This was a 16″ bore with a 20″ stroke, 4-stroke direct reversing engine. An Elliot-Buchi turbocharger helped the engine make 1200HP at only 275RPM. These engines have a very unique sound to them, a slow rhythm with the slight turbo whistle in the background. Here is a great video/audio of an Enterprise DMG-36, the next size engine down, but a great demonstration of the sound of these engines, posted by Youtube user Alain1554.

https://youtu.be/587D1qs2WTE?si=JaJgstiHgu0vop9v

The 14 tugs would all be named after majors of the US Army. Jakobson built theirs between April of 1943 and March of 1944 were the: LT-1, Major Ethel A. Robbins, LT-2 Major Randolph J. Hermandez, LT-3 Major Ralph Bogle, LT-4 Major Wilbur F. Browder, LT-5 Major Elisha K. Henson, LT-6 Major Ocea L. Ferris, LT-7 Major George W. Hovey & LT-8 Charles A. Radcliffe. Tampa Marine would build theirs also starting in April of 1943, and finishing in October. Their tugs were the: LT-18 Major Emile H. Block, LT-19 J.H. Hickey, LT-20 Major Robert W. King, LT-21 Major Otto I. Lantry, LT-22 Major E.J. Maloy, LT-23 Major C.A. McGarrigle.

The tugs were covered in the August 1943 issue of Pacific Marine Review. Click for Larger. San Francisco Public Library Collection.

Unfortunately, Photos of these tugs in their Army life are hard to come by! This is the LT-3 at work in her post war white paint scheme. Click for larger. Photo by Richard/Flickr

Navsource maintains pages on all of these tugs individually at: https://www.navsource.org/archives/30/15/15idx.htm

These tugs went right to work for the war effort, with several being present for the Normandy Beach invasion in June of 1944. 3 of these tugs would be transferred to the Army Corps of Engineers, and put to work on the Great Lakes. The LT-4 Major Wilbur F. Browder became the Ludington, LT-5 Major Elisha K. Henson became the John F. Nash and the LT-18 Major Emile H. Block became the Lake Superior. Amazingly enough, all 3 of these tugs would become museum ships after their careers with the ACOE ended.

ACOE Tugs – Museum Ships

The John F. Nash was retired by the USACOE in 1989 and became an exhibit at the H. Lee White Maritime Museum in Oswego New York. The tug was restored to her US Army grey, and renamed as the LT-5 once again. The tug is open for tours in the summer months, and the museum is well worth a stop. Click all photos below for larger.

https://hlwmm.org/pages/the-lt-5-major-elisha-k-henson

https://gltugs.wordpress.com/lt-5/

The tug is on display in Oswego, New York, just outside of Lock 8 on the Oswego Canal.

The LT-5 still is setup with an Engine Order Telegraph system, where the captain would ring bell commands to the engineer, who in turn controlled the engine. The captains cabin (center), is usually the nicest room on the tug, however all of these staterooms are a good size, with plenty of room for a crew.

The galley on the LT-5 is a bit more original then the Ludington, and still has her large cast iron Webb stove in the aft corner. A wall has been added in the back of the sink/pantry area.

The LT-5 is still maintained operationally, however I do not know how often the tug is started and run these days. Either way, she is in fantastic shape for her age.

———-

The Lake Superior was retired by the USACOE in 1995 and became an exhibit at the Duluth Entertainment & Convention center in Duluth, MN behind the museum ship William A. Irvin. The tug was sold to Billington Contracting in 2007, and removed from display. The tug has been listed for sale for a few years, and unfortunately sank at her dock in 2022. The tug was raised, and has been sitting since with an unknown future. https://gltugs.wordpress.com/lake-superior-2/

———-

The Ludington was retired in 1995, and sold to the City of Kewaunee, WI. The tug was restored and put on display in downtown, where it is open for self guided tours in the spring/summer months. Lets take a deeper dive on the Ludington. https://www.kewaunee.org/tug-ludington

The tug is docked on the Kewaunee waterfront, where for a few dollars you can walk through the tug. Note the additional sun shades added under the visor by the USACOE. While I am sure they were a welcome addition for not staring into the sun on the lake, in my opinion they detract from the lines of the wheelhouse.

These tugs have a really nice interior layout. I was never a fan of aft galley tugs, however this one is rather nice and well laid out, with a huge galley area (aft) and plenty of seating (forward). Unlike the LT-5, this galley has been slightly modernized.

There is 4 staterooms on the main deck, as well as the captains cabin behind the wheelhouse, as well as forepeak berthing. The tug is still essentially as it was on her last day of service.

On the upper deck aft are the towing machine, capstan and another set of propulsion/steering controls.

Towing machines on tugboats was still a novelty in the era when this tug was built, the towing wire exits the upper aft end of the deckhouse through a set of fairleads. Up the bow, is also a large capstan, which doubles as an anchor windlass.

The tugs have a rather large stack, with paint lockers on either side. A modern inflatable life raft sits on top of the clerestory.

Unlike the Nash above, the Ludington was upgraded to have full pilothouse engine controls, with an air throttle on either side of the wheelhouse. Steering was provided by an American Engineering Electric-Hydraulic system.

All of the pilot air and valves are mounted on a nice board in the forward end of the upper engine room. The tugs builders plate is on the back wall.

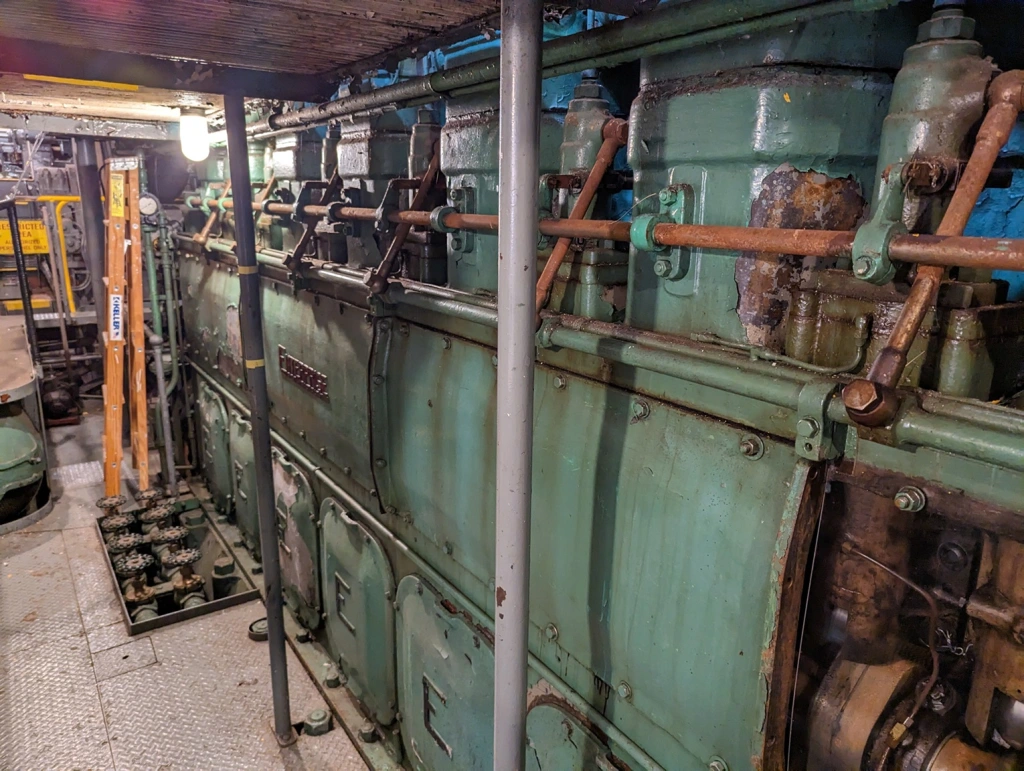

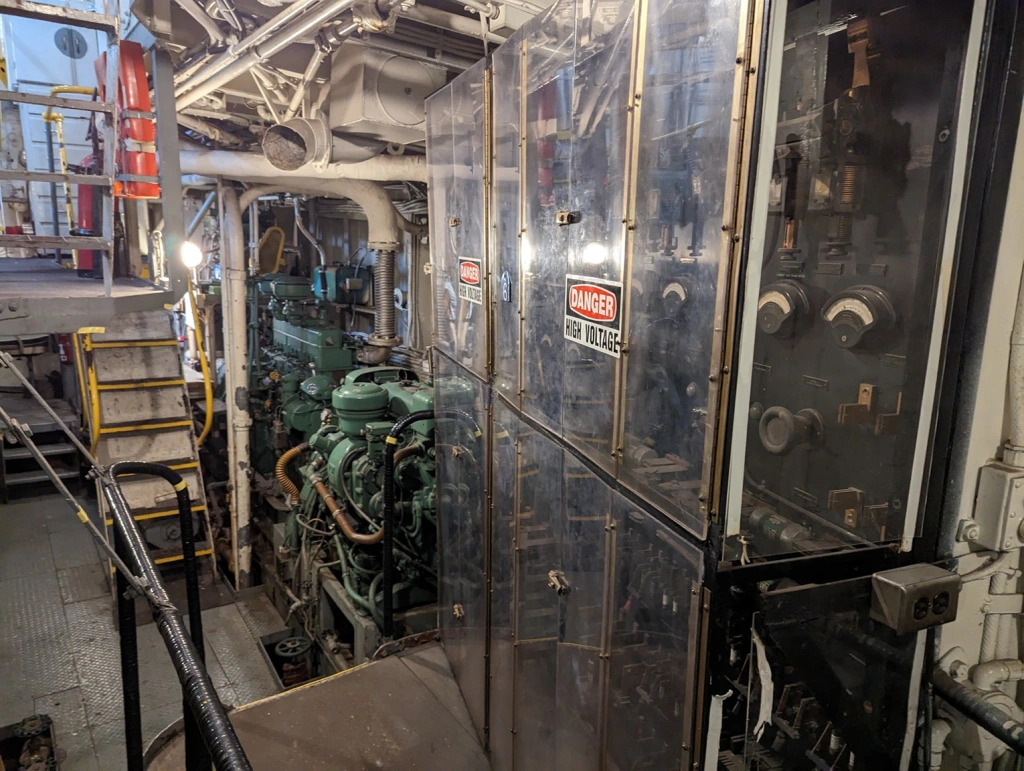

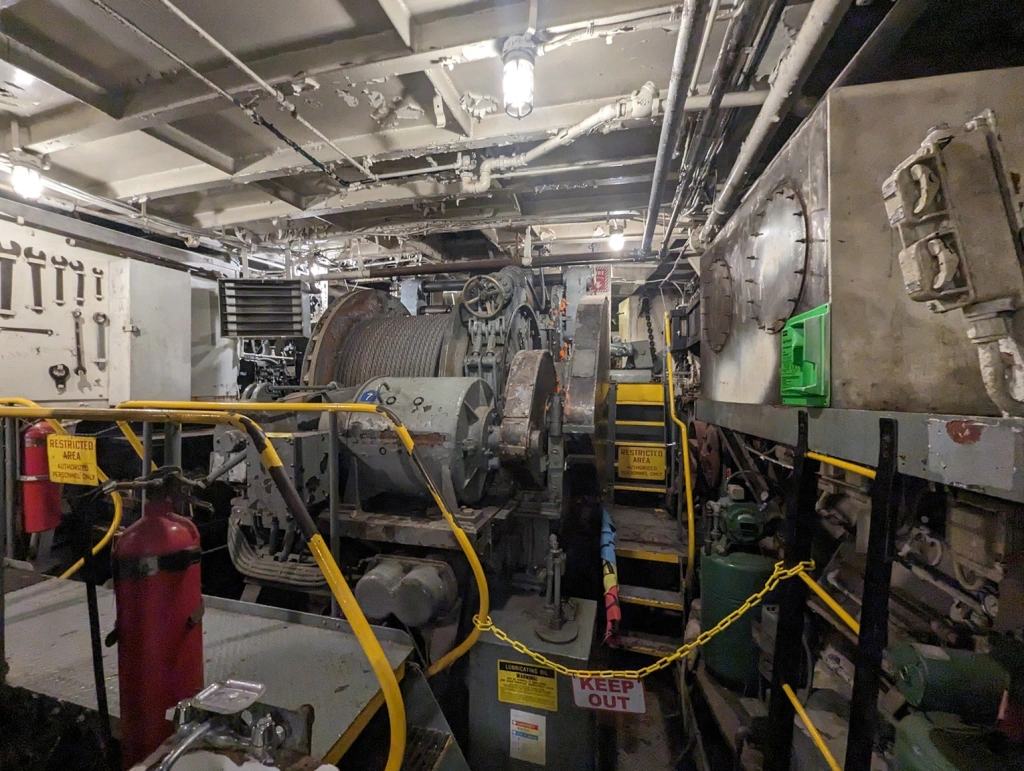

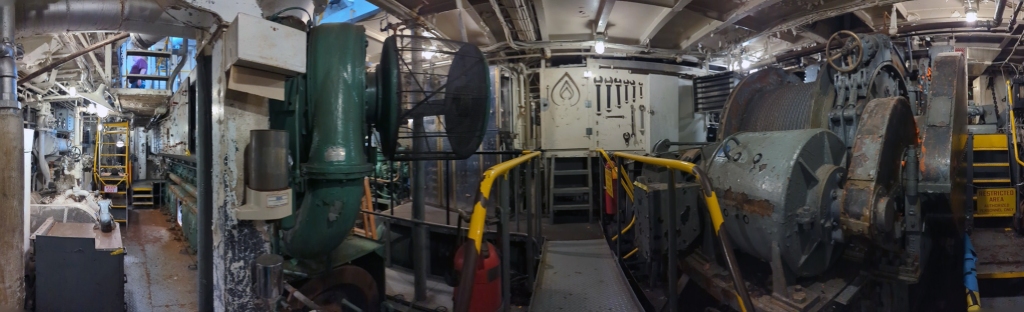

The tugs have a unique two level upper engine room, with platforms on either end. You enter from the starboard side of the galley, and step down onto a landing. The forward end has another landing that takes you into a central hallway for access to the staterooms.

You do not get a sense of scale as to how big these Enterprise engines are until you are standing next to one!

(left) The port side of the tug has a large 3 cylinder compressor, as well as the heating boiler and oil filters. The starboard side (right) has the tug’s generators, the Superior up forward, and a Detroit 3-71 that was added later. The switchboard is aft of them, on a small raised platform, which takes you over the shaft.

The Enterprise used the Buchi system of turbocharging, one of the first developed. The turbocharger itself was built under license by Elliot, and was rated for 15,000RPM. Enterprise engines use a sliding camshaft (right) in order to change the timing and start the engine ahead or astern. The camshaft was originally moved forward and back with an air motor tied into the start lever.

In the after end of the engine room is the Almon-Johnson constant tension towing machine. A large DC motor powered this. These Almon-Johnson towing machines were incredibly popular after the war, with several surplus ones being installed on tugs right up until the 1980’s. On the flat behind the towing machine is the steering gear.

Enterprise Engine & Foundry was a popular west coast engine builder, who would receive several WWII contracts for propulsion engines. Unfortunately, they fell out of favor after the war, as smaller, higher horsepower engines were coming on scene. They found a smaller market in stationary service, however even those would fall out of favor by the 1970s. Cooper Machinery Services currently owns the rights to the engines, and supplies parts for those still around. The forward end of the engine was the control end, with the start lever and fuel controls on the right side. This tug has had all of this changed with the pilothouse control modifications and the installation of air cylinders to control the start/stop/speed.

A panorama of the engine room.

The Original Trio – Post War

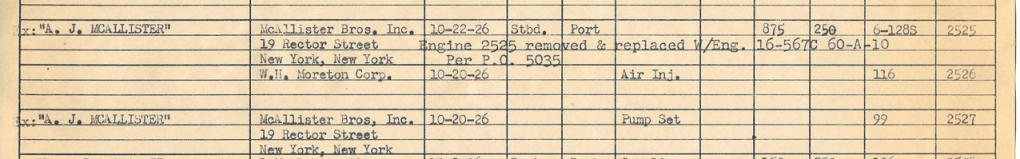

After the war was over, the original 3 tugs would be surplussed from their services. The Rowen Card/ YNT-12/Tamaha was returned in 1947 to Card Towing, however they were now owned by McAllister Towing (McAllister bought out Card in 1944) with the tug becoming the A.J. McAllister. The Dauntless #14/ YT-171/Yaquima was returned to Dauntless Towing Line. The Dauntless #15 however, did not return to Dauntless. She would stay on the west coast and become Andrew Foss.

Let’s take a quick look at these three original tugs in their post war careers:

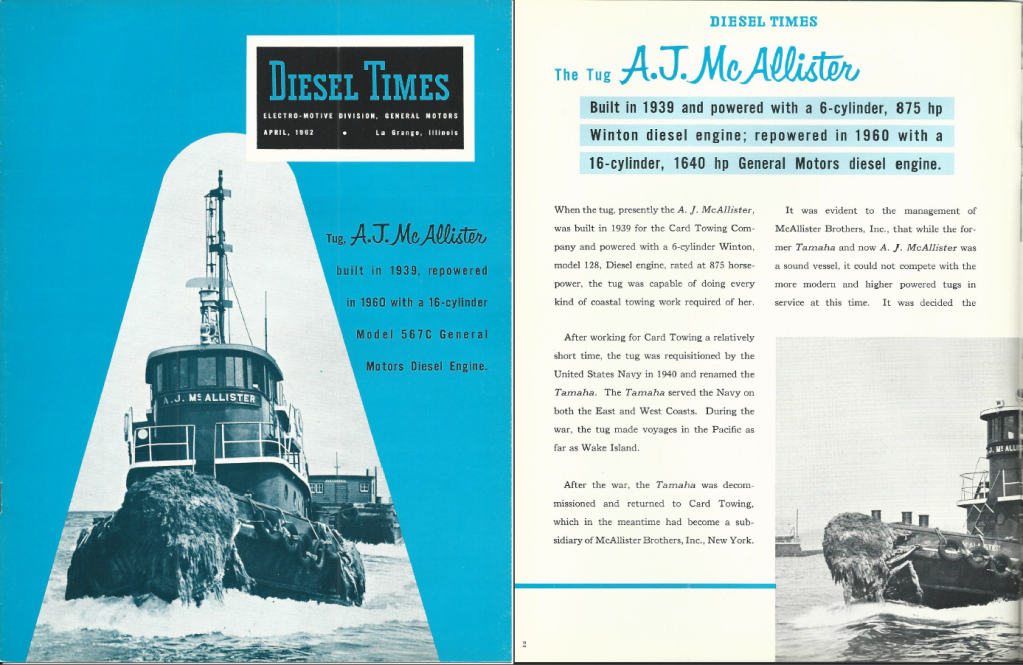

The A.J. McAllister would work in a pretty much untouched state for McAllister until early 1960. McAllister sent the tug to their own in-house shipyard – Tug & Barge Drydock Inc., where she was repowered with a brand-new Cleveland Diesel-supplied 16-567C. The new engine was rated for 1640HP, and drove a Falk 16MB Reverse-Reduction gear, bringing her from a direct reversing bell boat to a modern clutch tug. The only real change to the tug with the repower was the installation of a more slender, taller stack. In the late 1970’s, disaster struck the tug. After hitting a submerged object while taking an oil barge into Glenwood on the North side of Long Island, the tug took on water. They were able to get the tug to the Bronx Towing Line dock on the other side of the harbor to dewater it, however they could not keep up and the tug went down and rolled. The tug was raised, taken back to Tug & Barge where she was cleaned up, repaired and went back to work for another 20 or so years until being sunk as an artificial reef off the coast of New Jersey. Later in her career after the sinking, she received another, smaller streamlined stack.

The Winton-powered A.J. McAllister (left) is tied up in front of a then still steam-powered Ellen F. McAllister. The tug was repowered by McAllister in 1960, and received a new, narrower stack. Note that the front ladder was changed to a stairway. Click for larger. Both Photos – Dave Boone Collection

In the late 1970’s, the A.J. McAllister sunk in Port Washington, NY. The tug was raised, fixed and went back to work. The tug is off to a job in 1982 (right), now sporting a new, slightly streamlined stack. Click for larger. Left: Bob Mattsson photo, Right: Jim Devin Photo

The A.J. was featured in Diesel Times, what was the Cleveland Diesel Engine Division monthly newsletter. The tug was repowered in 1960 under Cleveland, however was not featured until 1962, by then the newsletter was part of EMD. Click for larger. Jay Boggess Collection.

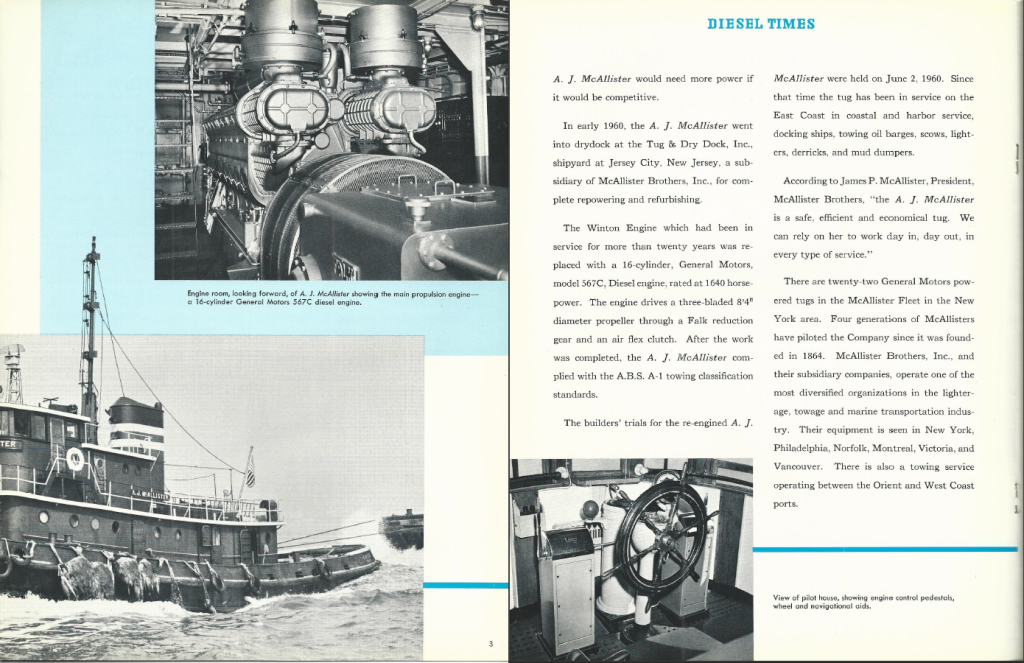

The Dauntless #14 returned to New York Harbor in 1946 to Dauntless Towing, where she was returned to her original name. In 1949, the tug was repowered with a Cleveland 16-278A with reverse/reduction gear and air clutches. This was a factory rebuilt engine, originally out of Landing Ship Medium (LSM) 152, shipped 5/15/1944. The engine was rebuilt and resold on 12/22/1949. Dauntless Towing was purchased by Moran Towing in 1955, where the tug was renamed as the M. Moran. The tug was transferred to their Curtis Bay Towing subsidiary in 1960 where the tug was renamed Lambert Point. The tug made it back to the Moran fleet once more in 1970, being renamed the Claire Moran. The tug was scrapped in 1991.

Note that once again, the same publicity photo was used as was used back in 1942, this time as a single page feature in Diesel Times. Jay Boggess Collection.

Left: Now working in the Curtis Bay Towing fleet as the Lambert Point, the tug was relatively unchanged from as built. Right: The tug finished out her life in New York Harbor, by then on her last life. The outside wheelhouse steps were removed, and the top stack coaming cut down. Click for larger. Both Photos – Dave Boone Collection

Dauntless #15 stayed on the west coast, ultimately being sold to Foss Tug & Launch Company where she became Andrew Foss. Foss repowered the tug with a 16-567C engine. The tug was sold by them in 1975 to Western Towboat, who renamed her the Panchena. After bouncing around the Pacific Northwest with various marine contractors, the tug wound up abandoned and aground in Alaska after being used as a liveaboard for a few years, ending with the name Lumberman. The tug was towed offshore and sunk by the USCG in 2021.

The Dauntless #15 led a long life after the war, but succumbed to abandonment at the end. After being beached and left to die, the tug was salvaged, cleaned and sunk offshore. Click for larger. Photos by Gillphoto/Wikipedia

Post War Survivors

Outside of the museum ships and the trio above, of the original tugs, 7 of the 8 Jakobson tugs returned stateside after the war, and 2 of the Tampa tugs. Here is a quick look at a few.

The LT-2/LT-2 Major Randolph J. Hermandez was sold to Dauntless Towing line, to replace their original Dauntless #15 that was requisitioned by the Army. They would name the tug – you guessed it, the Dauntless #15. When Moran took over, the tug became the Julia C. Moran briefly before being transferred to Curtis Bay Towing, where she gained the name Sparrows Point. The tug was chartered to Transit Oil and renamed the Accomac. The tug was returned, and put into the Moran fleet as the Doris Moran briefly before being sold to Crescent Towing of New Orleans, where the tug spent her last few years working as the Sparta. Her ultimate disposition is unknown.

Curtis Bay Towing was a subsidiary of Moran Towing, and worked the ports of Philadelphia, Baltimore and Norfolk. The tugs varnished wheelhouse window frames accents the companies white and blue nicely. Like the Lambert Point, the tug had her outside wheelhouse steps removed at some point in her later years. Click for larger – Dave Boone Collection

Called the Accomac, the tug spent a few years, likely under a charter arrangement for Transit Oil. The tug was repowered during her Curtis Bay years, however I am not sure what with, unfortunately. Click for larger – Dave Boone Collection

Crescent Towing & Salvage in New Orleans had the LT-7 Major George W. Hovey. The tug spent her post -Army career with the Army Corps of Engineers (unlike the tugs above, she did not go to the Great Lakes) as the San Luis II. Crecent purchased the tug in 1978, and renamed her as the Terence J. Smith. The tug was repowered with a GE 16-cylinder FDL engine. She spent her last years doing ship assist work in New Orleans, and sunk in the fall of 2009. The tug was raised and scrapped a few months later. Click for larger – VDD Collection

New York’s Tracy Towing Line wound up with the LT-8 Charles A. Radcliffe in 1948 after the war, naming her the Kathleen C. Tracy. Tracy’s main work was moving coal barges around New York Harbor. The tug did not last long with Tracy. In 1956, Tracy had a brand new tug built by Levingston Shipbuilding, which would take this tugs name. The tug was sold to Crowley’s Shipowners & Merchants Tugboat Company (Red Stack) on the West Coast, and renamed the Sea Lion. She unfortunately would sink in 1964. Click for Larger – Dave Boone Collection